Delivery from $80

Worldwide Shipping Available

Free Pickup from Seaforth NSW

Previous

Next

Wood

80 x 10 cm

A$2,800 Buy NowAcrylic on Linen

152 x 183 cm

Sold SoldAcrylic on Linen

152 x 183 cm

Sold SoldAcrylic on Linen

182 x 152 cm

Sold SoldAcrylic on Linen

152 x 152 cm

Sold SoldAcrylic on Linen

122 x 152 cm

Sold SoldAcrylic on Linen

122 x 152 cm

Sold SoldAcrylic on Linen

152 x 152 cm

Sold SoldAcrylic on Linen

152 x 152 cm

Sold SoldAcrylic on Linen

152 x 152 cm

Sold SoldAcrylic on Linen

152 x 152 cm

Sold SoldAcrylic on Linen

152 x 152 cm

Sold SoldAcrylic on Linen

152 x 152 cm

Sold SoldAcrylic on Linen

152 x 152 cm

Sold SoldHaven't found what you're looking for?

Contact a consultant about other ways to acquire an artist's artwork.

Acrylic on Linen

91 x 165 cm

A$6,800 Buy NowAcrylic on Linen

56 x 71 cm

A$6,000 Buy NowAcrylic on Linen

152 x 121 cm

A$11,000 Buy NowAcrylic on Linen

122 x 152 cm

A$22,000 Buy Now

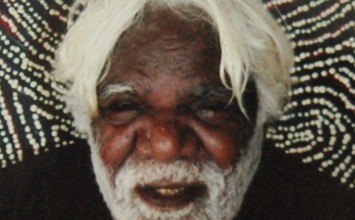

Born circa 1947

Region Pintupi

Language Pintupi

George Ward Tjungurrayi was born in Kiwirrkura around the year 1945. George and his older brother, Willy Tjungurrayi, who is also a senior Pintupi painter, moved to Papunya in the 1960s. He was brought into Papunya in 1962 by the Northern Territory patrols which Jeremy Long was in charge of after watching local artists painting at that time.

George began painting for the Papunya Tula Artists in 1976, at the West Camp of Papunya where the nomadic desert people stayed and at various locations, including Mt Liebig (Yamunturrngu) and Kintore (Walungurru), and the Yayayi and Waruwiya outstations, working alongside Joseph Jurra Tjapatjarri and Ray James Tjangala.

His paintings are striking Tingari stories, done in linear optical stripes and square patterns. The depictions and designs in his works have brought him into prominence and are now highly sought after by collectors and galleries worldwide. George currently lives at Wallangarra (Kintore), Northern Territory. He is brother to Natta Nungurrayi. His son is Jake James Tjapaltjarri also a collectible artist.

George Ward is a reticent and silent Western Desert man. This cast of character can cause the odd practical problem, now that he has become one of the nation’s most admired and most keenly collected artists: He’s not at home in English; sees no merit in photographs; is uneasy in big, bustling towns like Alice Springs. “I’m a bush man, me,” he insists, with a distinct, proud edge in his voice.

George’s father died while he was still very young. It was only in his teenage years that he first encountered Europeans, when a commonwealth welfare patrol came upon his family group camped by a desert waterhole. After travelling to the government settlement at Papunya, first home of the desert painting movement, Ward worked briefly as a fencer and a butcher in the community kitchen. He also met and married his wife, the somewhat formidable Nangawarra, a member of one of the desert’s most dominant families.

Once their first child was born, the couple moved west to Warburton, then on through the ranges to Docker River, to Warakurna and at last to the newly established Pintupi capital of Kintore, in the looming shadow of Mount Leisler, where they still spend time today.

It was here, just over a decade ago, that Ward first painted on canvas: a handful of elegantly “classical” concentric roundel works from that time survive. But it was only over the past three years, after the death of his brother, Yala Yala Gibbs, a celebrated artist, that the responsibility to paint fall squarely on Ward’s shoulders. By this stage, he was a senior desert man: He lived deep in the world of law. The canvases he began producing for Alice Springs-based Papunya Tula artists were like nothing else that had come before in the desert art movement: sombre, cerebral, full of grave intellect.

One of George’s most recent achievements is winning the prestigious 2004 Wynne Prize at the Art Gallery of New South Wales for his topographical depiction of the Western Desert. He has also exhibited in many galleries throughout the past decade.

National Gallery of Victoria Indigenous Art Curator, Judith Ryan quickly caught their splendour. “He hit on this sophisticated, geometric, filled-in style almost at once,” she says. “I have the sense that he began to paint only when he was ready, in full command of both story and country – and he seems able to harness considerable power and visual energy almost every time he approaches a large canvas.” Once Ward has blocked out his painting’s various fields, he fills each one with parallel lines, tight-drawn. They have the feel of contours, making up recurring patterns: wavy paths, tilted circles, chevrons. This underpainting process can be protracted. The work still bears no resemblance to its final form.

Then he takes up his dotting stick. A transformation begins. At last, after several days of meticulous detailing, the shimmer of the finished surface begins to show. Ward’s large-scale works depict the ancestral desert narratives, relating to the country west of Kintore – above all, the snake-rich landscapes around Lake MacDonald. But they are not maps, as much as expressions of a world, logic, a sense of how space is enlivened by spirit.

Just as the creation journeys they refer to operate on many levels, so do the paintings: to the outside eye, they possess an austere beauty; when explained in detail, they can serve as visual clues to a complex story-system; but all the while their air of coherent depth comes from the underlying mental architecture of the desert world, most of whom have passed away. It describes journeys taken by the Tingari ancestors – men, women, children, dogs – who once moved through the landscape, but are all transformed, now, into rocks, or water-snakes. A cataclysmic storm fell down upon them: black clouds, rain, lightning. Gradually, a complex narrative emerges, which involves shifting of shapes, claypans formed by nose-blowing, descent of figures from the sky. Many things are said of Ward’s canvases, both by him and by his immediate family.

Ward’s brother-in-law, Frank, for one, advises that the artist paints some canvases in a pinkish palette because the colour feels “strong and balanced”, while the black colour is chosen because it’s “good and healthy”. Then again, black and pink stand respectively for winter and for summer landscape, and much more. Western eyes interpret differently, and notice other things. Anita Angel, curator of the Charles Darwin University Art Collection, and a prominent collector in her own right, greatly admires Ward, while gauging his paintings largely in formal terms. “It’s instantly recognisable, he has a style, but it’s more than just a style,” she says. “He’s coming from somewhere deep within his mind’s eye. To draw out what he does. He’s not experimenting, he knows exactly what he’s doing; he has something to say about what he sees, and feels, and knows.”

Angel suspects a connection between Ward’s spare imagery and the incisions made upon the material objects of desert culture: ritual items only vaguely known to outsiders. This obscure, shielded element that so clearly lies within Ward’s work makes all the more striking his strong appeal to serious collectors of contemporary art. Melbourne Gallerist, Gabrielle Pizzi, who has included significant pieces by Ward in four recent shows, believes his work can jump the cultural divide because of his capacity to fuse the desert tradition with an individual, almost private quality. “He’s got it,” she says, “both the Pintupi grounding, and the genius to paint in ways that are innovative and exciting. He takes desert painting to another level. In the gallery people stop still in front of his works. They respond to the power, the purity and the intent.”

EXHIBTIONS

1997 Utopia Art, Sydney – Solo show

1998 Gallery Gabrielle Pizzi, Melbourne, Australia

2010 Trevor Victor Harvey Gallery, Sydney Australia

2010 Linton & Kay Fine Art Gallery, Perth Australia

GROUP EXHIBTIONS

1990 Friendly Country – Friendly People, Araluen Centre for the Arts, Alice Springs, Australia

1991 Araluen Centre for the Arts, Alice Springs, Australia

1992 Broadbeach, Australia

1993 Canberra, Australia

1994 Broadbeach and Adelaide, Australia

1995 Canberra, Australia

1995 Dreamings – Tjukurrpa, Groninger Museum, Groningen,The Netherlands

1995 Museum & Art Gallery of the Northern Territory, Darwin

1995 Papunya Tula Artists Pty. Ltd., Alice Springs

1995 Australia Utopia Art Sydney, Australia

1996 Adelaide Fringe Festival, Papunya Tula Artists Pty. Ltd., Adelaide

1996 Araluen Centre for the Arts, Alice Springs

1996 Gallery Gabrielle Pizzi, Melbourne

1996 Museum & Art Gallery of the Northern Territory, Darwin

1996 Nangara. The Australian Aboriginal Art Exhibition, Brugge, Belgium

1996 Papunya Tula Artists Pty. Ltd., Alice Springs

1997 Gallery Gabrielle Pizzi, Melbourne

1997 Geschichtenbilder, Aboriginal Art Galerie Bähr, Speyer, Germany

1997 Papunya Tula Artists, Alice Springs, Australia

1998 The Desert Mob Show, Araluen Centre for the Arts, Alice Springs, Australian

1999 Aboriginal Art, IHK WÜrzburg, Deutschland (in Kooperation mit Aboriginal Art Galerie BÄhr, Speyer)

2000 Art of the Aborigines, Leverkusen, Germany (in cooperation with Aboriginal Art Gallery Bahr, Speyer)

2000 Lines, Brisbane, Queensland

2000 Papunya Tula: Genesis and Genius, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney

2000 Pintupi Men. Papunya Tula Artists, Alice Springs, NT, Australia

2001 Art of the Pintupi, Adelaide

2001 Kintore and Kiwirrkura. Gallery Gabrielle Pizzi, Melbourne

2001 Palm Beach Art Fair, Palm Beach, Florida, USA Papunya Tula

2001 Melbourne, Australia

2004 Art Gallery of NSW- Wynne Prize

AWARDS

2004 Wynne Prize – NSW Art Gallery

AUCTION RESULTS

Highest Auction Price – $42,000

59 works have sold at auction since 2004

COLLECTIONS

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne purchased 1997

Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney

Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide

Musée des Arts d’Afrique et d’Océanie, Paris, France

Groninger Museum, Groningen, The Netherlands

Artbank

Museum of Victoria, Melbourne

Robert Holmes a Court Collection, Perth

Supreme Court of the Northern Territory, Darwin

LITERATURE

Friendly Country – Friendly People. Kimber, R. (Hrsg.), Araluen Centre for the Arts, Alice Springs 1990,. Johnson, V.

Aboriginal Artists of the Western Desert. A Biographical Dictionary, Craftsman House, East Roseville 1994, ISBN 9768097817 pg204

Nangara. The Australian Aboriginal Art Exhibition from the Ebes Collection. The Aboriginal Gallery of Dreamings (Hrsg.), Melbourne 1996,. Stourton, P. Corbally,

Songlines and Dreamings. Lund Humphries Publ., London 1996, ISBN 0853316910

Papunya tula Genesis & Genius – Published by AGNSW 2000 pg 120,121,180, 181, 195, 227, 281, 294

Contemporary Aboriginal Art by Susan McCulloch. Published by Allen and Unwin 1999, pg 63

ARTICLE OF INTEREST

“Going to the source”,

2004, April 20th, The Australian

By Nicolas Rothwell

Harvey Galleries cordially invite you and your guest to join us for the FIRST solo exhibition by Wynne Prize winner George Ward Tjungurrayi. Continue reading

Continue readingSubscribe to recieve the latest updates from George Ward Tjungurrayi

Harvey Galleries was founded by the Harvey family in 1994 with an eye to establish a dynamic and inclusive contemporary art space on the North Shore of Sydney. For almost three decades we have expanded our reach to over three gallery locations and an ever expanding stable of the best artists Australia has to offer.

Harvey Galleries acknowledges the traditional custodians of the lands upon which our galleries stand. The Guringai people (Seaforth), the Gadigal people of the Eora Nation (Sydney), and the Bunurong Boon Wurrung and Wurundjeri Woi Wurrung peoples of the Eastern Kulin Nation (Melbourne).

We pay our respect to Elders past and present.

Always be the first to know about exhibitions, events and new art releases.